Antarctica is surely one of the most beautiful places on earth, with its pristine ice sculptures, creaking cliffs, breathtaking shorelines, dazzling blue skies and diamond dust (a fine precipitation of ice crystals which can form spectacular haloes and mirrored solar images known as sun dogs). Almost half of the Antarctic coastline is composed of ice shelves suspended above the ocean, creating a magnificent blue wall rising from the sea. There are only two seasons on the continent, summer and winter, and both receive very little rain or snowfall. As well as being extraordinarily beautiful, Antarctica is teeming with wildlife in the summer, largely due to one small crustacean which flourishes in the relatively warmer waters: krill.

Sea ice formation during the winter is not constrained by surrounding landmasses in the Antarctic, so it spreads over a much larger area than in the Northern Hemisphere before melting, progressively shrinking and breaking up in the Antarctic summer season from October until February. The ice serves as habitat for algae, which live on and inside the floating ice, turning it brown or greenish. This is vital sustenance for polar wildlife such as krill, which in turn are eaten by so many other, considerably larger species. Penguins and seals also depend on sea ice for breeding, feeding, and shelter. As a result, enormous colonies gather on its fringes.

While most of the continent is covered in a dense layer of ice almost 2 km (6,000 ft) thick, the Antarctic Peninsula in the far north of the continent has extensive areas with no ice covering. In summer, this region looks much like Iceland and Canada do in winter.

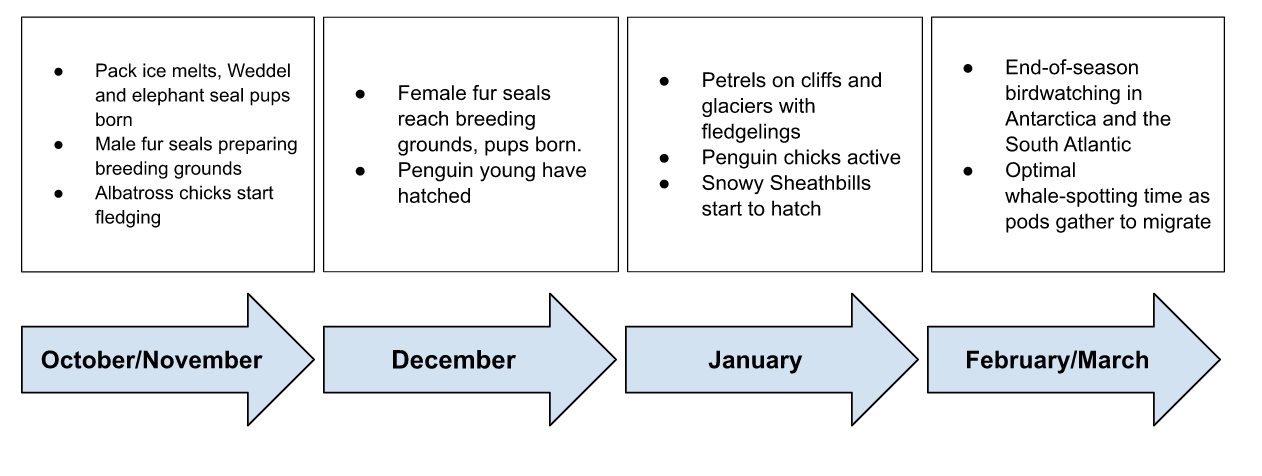

Month by month

Mammals and their young

-png.png?width=500&name=antarctica%20(3)-png.png)

Source: Canva

If you are traveling to the Antarctic, you can expect to see the world’s largest marine mammals emerging majestically from the waters. Up to eight species of whale are present throughout the Antarctic, including the humpback, the orca, and the blue whale. Although present throughout the summer, the best time to spot them is at the end of the season in February and March, when they gather in large pods of hundreds in preparation for their migration north. Popular spots are Drake Passage and the spectacular Lemaire Channel, but most especially the whale hotspot, Wilhelmina Bay (also known as ‘Whale-mina Bay’), where krill is in plentiful supply.

There are six species of seal in Antarctic waters, the rarest being the Ross seal. The most predatory is the leopard seal, which loiters on the edges of the pack ice in wait for its favorite meal, the Adélie, which is the most widespread penguin species. There are no prizes for guessing what the Crabeater seal likes to eat best: it uses its rune-like serrated teeth to strain crustaceans out of the seawater.

-jpg.jpeg?width=500&name=pexels-josy-mol-9695915%20(1)-jpg.jpeg)

A Weddel Seal. Source: Pexels

Weddel seals haul themselves out onto the ice to rest, molt, or give birth. The monogamous females usually have one pup in September or October. New-born Weddell seal pups are little scraps of fur with huge eyes and Weddell seal milk is one of the richest produced by any mammal, containing about 60% fat, so they grow into their loose-fitting skins very quickly. The mothers encourage their pups to start swimming at about two weeks old and they are weaned at seven weeks, after which they are left to fend for themselves. They spend more time in the water than out, as with their thick blubber they are more comfortable there than on the windy ice, where temperatures can drop to -40° C.

The largest pinniped is the southern elephant seal. In September and October, pregnant mothers come ashore to birth a single pup each. The pups are weaned after three weeks and remain onshore in groups for about eight or ten weeks before taking to the sea.

The Antarctic fur seal has visible ears, and so is actually a sea lion. The largest congregation occurs on the island of South Georgia and they also gather on the South Shetland, Orkney and Falkland Islands in winter. The polygamous males establish breeding grounds from October to early November, the pregnant females arrive in December and 90% of pups are born in the same 10-day window before being weaned at about four months old.

Chick-rearing

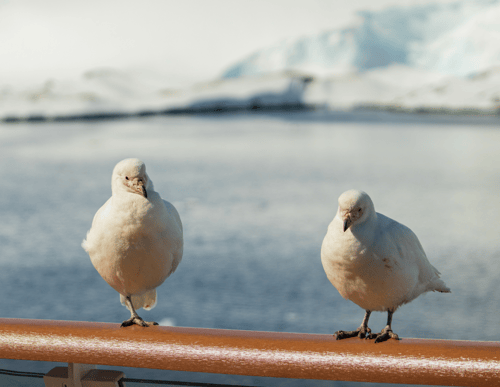

The snowy sheatbill. Source: Canva

There are 46 species of birds in Antarctica, and several are unique to the region: Apart from penguins, the pink-faced/snowy sheathbill is the only land bird native to Antarctica. It looks a bit like a white grouse and is omnivorous, often scavenging carrion, living along rocky reefs off the main continent and the surrounding islands. Snowy sheathbills lay two or three eggs between December and January, which hatch a month later, and leave the breeding sites after the summer season.

Seventeen species of penguins can be seen in Antarctica and they hop onto land in summer to spend some quality time with the family. If you get the chance to go ashore to visit a penguin colony, you will experience vast and busy crowds of these cheeky, chattering chappies with their cheerful, wooly chicks. Only two species (emperor and Adélie) are true Antarctic birds, although others (chinstrap, gentoo and macaroni) breed on the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, where around twelve million penguins live in the somewhat milder climate. King penguins only breed on the warmer sub-Antarctic islands further north, especially South Georgia.

Source: Pexels

Most penguins lay their eggs in the early spring (November/December), so the best time to see chicks and fledglings is mid-season, although they are present in the extensive King Penguin colonies on South Georgia throughout the season. This is also the place to see three Albatross species nesting, again at any time in the summer. The black-browed albatross breeds in large colonies on hillsides and takes five and a half months to raise its young. The largest breed, the wandering albatross, fledges in November and December.

Petrels, prions, fulmars and shearwaters gather in great numbers in summer, nesting on scattered sub-antarctic islands and ice-free places. Petrel means “little Peter” and they are so named due to their peculiar way of pattering their feet on the water, effectively walking on it: much like Christ’s Apostle Peter, who apparently accompanied the son of God as he walked on the waters of the Sea of Galilee. Antarctic petrels return to their nests high on cliffs and icebergs in October to November, laying a single egg, which hatches in mid-January. The parents continue to feed the chick until it becomes independent in early March.

This is when the days grow shorter, and the Antarctic wildlife prepares for the Polar winter. Temperatures drop, although there is still little snow. After the endless summer sun, the end-of-season sunsets are spectacular.

You can tailor your Antarctic experience of a lifetime to experience the best for yourself: ask Polartours for the availability of your chosen route.

For example, active adventurers can explore the continent on foot, get up close and personal with penguins in their natural habitat and even camp out overnight:

Explore the Antarctica Basecamp!

And to experience extraordinary colonies of King Penguins, elephant seals and other unique wildlife, there is no better place than South Georgia.